This blog is going to serve as a progress report of my understandings related to the C++ programming language.

What should one expect?

- A beginners daily(~ almost) report on C++

- A lot of mistakes

- Some insights which will surely be redundant to a professional C++ programmer.

I am following this playlist on C++ and also would try to link various blog posts as I go along.

C++ compilation and linking

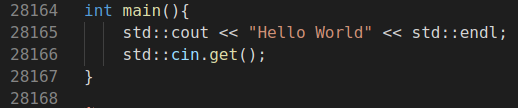

Once you have your environment setup, fire up your favourite IDE and then write the hello world program(follow the culture).

#include <iostream>

int main(){

std::cout << "Hello World" << std::endl;

std::cin.get();

}

Name this file whatever you want, I will keep it simple and name it hello.cpp. Once we have our source code we need to compile this. Compilation is a process to transform a high level language into machine level language (the 1s and 0s). The compilation process in C++ is rather well structured and logical. Let’s go through this one step after the other.

Pre-processing

In a C++ file we have a lot of pre-processor statements. These statements have a # prefixed to them. In the first stage of compilation the cpp(C pre processor) expands the pre-processor statements, deals with the macros and converts the small code file(source code) into a valid code file that the g++(GNU compiler) can compile.

$ cpp hello.cpp > hello.i

The file hello.i has ~28k code lines. The iostream library is copied and pasted where the #include statement resides.

Compiling to assembly language

Once the pre-processing is done, the code needs to be compile to assembly language. Assembly language (or assembler language), often abbreviated asm, is any low-level programming language in which there is a very strong correspondence between the instructions in the language and the architecture’s machine code instructions. The asm is dependant on the architecture of the processor.

$ g++ -S hello.i

This command creates a hello.s file. If you are curious, about how the code looks like, here it is.

.file "demo.cpp"

.text

.section .rodata

.type _ZStL19piecewise_construct, @object

.size _ZStL19piecewise_construct, 1

_ZStL19piecewise_construct:

.zero 1

.local _ZStL8__ioinit

.comm _ZStL8__ioinit,1,1

.LC0:

.string "Hello World"

.text

.globl main

.type main, @function

#truncated...

One step of compilation is done. We have successfully compiled our hello.cpp to hello.s.

Assembling to object code

With our assembly level code at hand, we can compile this into object code. This is where the assembler comes into play. The assembler takes in the assembly level language and assembles(read compiles) into the object code. The object code is the machine level code that the machine understands.

$ as -o hello.o hello.s

The object code is the final compiled machine level code that we want from the source hello.cpp file written.

Linking

After the code is compiled, the object files are given to the linker. The linker takes in different object files and links them together. Linking is necessary as different symbols are linked and each modules is compiled into one application.

$ ld -o hello hello.o

The linker after linking the different object files, outputs an executable. ./hello is the trigger that can be used to run the hello executable.

This blog is a comprehensive guide into the compilation and linking.

Variables

The basics that is there to variables is that they are data storage spaces. They memory location that data can be stored in are categorised by the virtue of their size. To designate the type of memory used we assign datatypes to each and every variable.

Some primitive type variables are:

- char, short, int, long, long long

- float, double

- bool

The size assigned by different data types depend on the compiler that you use. The following code snippet when run, would provide you with the size provided by your specific compiler.

#include <iostream>

int main(){

bool bool_variable = 0;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of char: " << sizeof(char) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of short: " << sizeof(short) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of int: " << sizeof(int) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of long: " << sizeof(long) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of long long: " << sizeof(long long) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of float: " << sizeof(float) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of double: " << sizeof(double) << std::endl;

std::cout << "[INFO] Size of bool: " << sizeof(bool) << std::endl;

std::cin.get();

}

The most intriguing discussion in terms of datatypes is that there are something called unsigned datatypes in C++. Let us suppose that with the int datatype, the compiler specifies a memory space of 4 bytes. One byte consists of 8 bits. Each bit can hold either 0 or 1. Now, with signed int 4x8 - 1 number of bits are used as storage. The one bit is kept to determine the sign of the number, that is whether the number is negative or positive. Hence the range of numbers we can store with an unsigned int is \(-31^2 <-> 31^2\). When we are certain that we would not like to store negative numbers, we can use the unsigned int which stores numbers between \(0 <-> 32^2\).